In this piece Professor Danny Dorling FAcSS explores some of the complexities and nuances of inequality in the UK. He shines a light on some compelling evidence which makes the case for progressive taxation and reforming education funding as essential ingredients of effective levelling up.

Levelling up taxation, funding and education

The human geography of the UK is a very unlevel playing field – more akin to a mountain range than a field. Inequalities vary greatly. Parts that you might not think of as especially unequal are in fact sometimes the most jagged of the socioeconomic mountains.

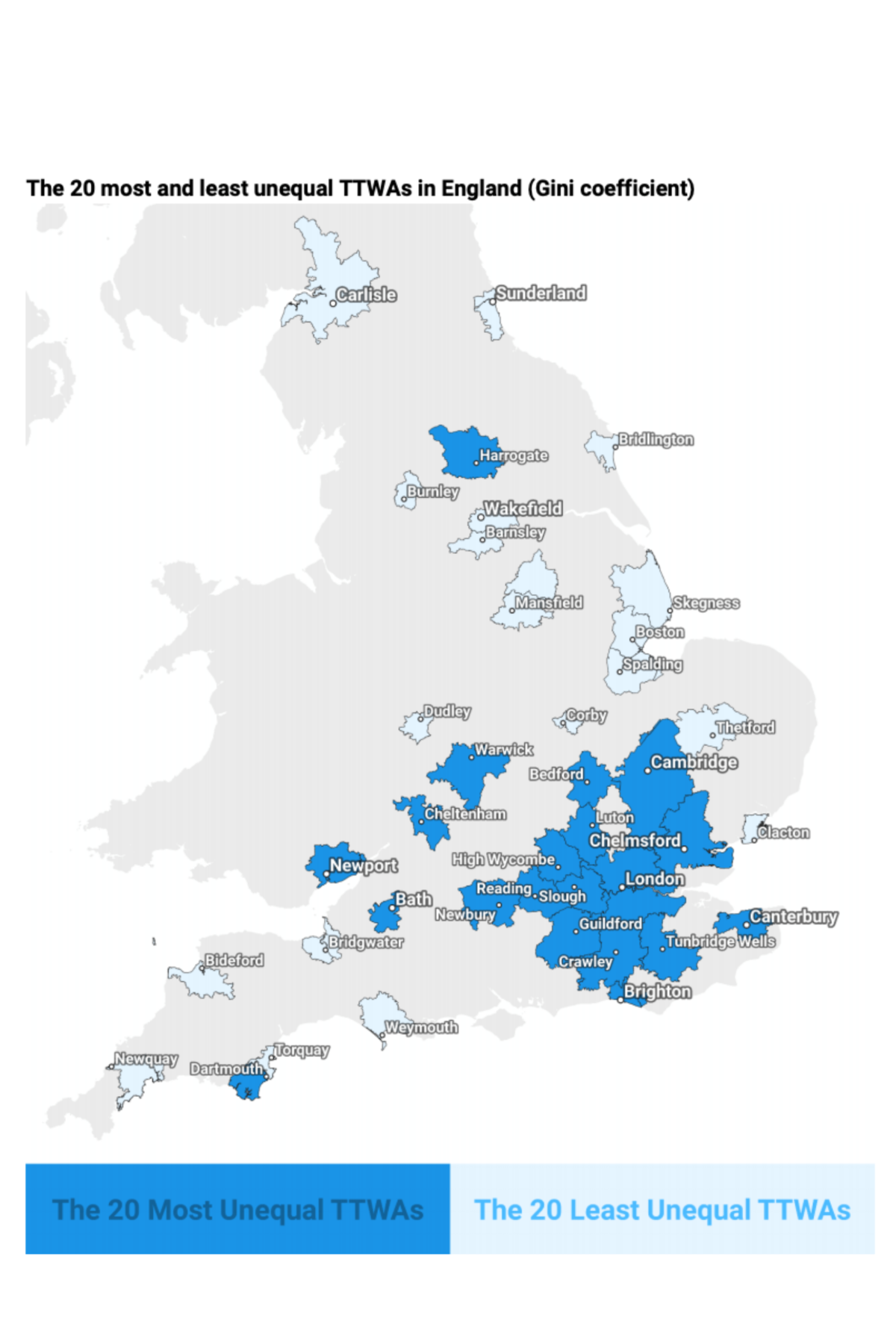

In 2019, Professor Alasdair Rae and Dr Elvis Nyanzu, of Sheffield University’s Department of Urban Studies and Planning, produced “An English Atlas of Inequality” for a wide range of different types of area across England. They found that local income inequalities were greatest, not in the poorest parts of that country, but in some of its most affluent cities and regions. Inequality within mostly poor communities tends to be low as there are usually few very well-off areas near areas which are mostly poor. Everywhere in the UK has some very poor areas. Prof. Rae and Dr Nyanzu gave Skegness, Sunderland and Bridlington as examples of low inequality areas.[1]

In contrast to poorer parts of England, they found that the five TTWAs (Travel-to-Work-Areas) with greatest inequality were, in rank order by Gini coefficient of income inequality: London; Tunbridge Wells; High Wycombe and Aylesbury; Slough and Heathrow; Guildford and Aldershot. (ONS’s 228 TTWAs approximate to self-contained labour market areas.)

Other areas of England with some of the highest inequality rates within them included Leamington Spa; Cambridge; Bath; Cheltenham and Oxford. Among the top twenty most economically unequal areas in England, the only one to be found in the north was Harrogate. A map of the 20 most and 20 least unequal areas on page 6 of their atlas reveals how London-centric gross inequality is.[2]

Within England, the greatest inequalities are thus found within some of the most affluent areas. These places always have relatively poor areas within them where people live who do many of the service jobs for those living in the more salubrious enclaves. The distribution of inequality found within Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland will be similar, but not quite as extreme. Levelling up the UK locally would require addressing the greatest inequalities first, which are geographically most concentrated in some of the most affluent parts of England.

The UK is not a poor group of countries but has a great deal of poverty within it because of factors such as excessive pay and relatively low taxation (when compared to other European countries). To truly level up, the need for extremely high incomes needs to be reviewed and reformed; gross inequality within institutions discouraged; and both earned and unearned income needs to be taxed more progressively. If this is not done, everyone living anywhere in Britain suffers. Economic inequality is socially corrosive.

People living in the shadow of some of the worst inequalities tend to suffer more than others. As one economist recently explained: ‘…median incomes in London, after housing costs, are no higher than elsewhere, and child poverty is considerably higher… [we now have] an increasingly dualised labour market, which has performed extremely well in creating jobs, but with many of those jobs being precarious or insecure, with the abuse of zero-hours contracts and self-employment in some sectors, growth of freelancing rather than employee jobs in others, and in a decline in training and development across the spectrum.’[3]

Perhaps the level of income inequality in Britain is natural?

The UK may be a very unequal place; but should we not accept that a high degree of inequality is now inevitable in a globalized world? Below are the 2018 estimates of household income inequality for 25 OECD countries (the 13 others have yet to report their figures for that year). Like some of the more equitable parts of Britain, some of the most equitable OECD states are poorer places, such as the Slovak and Czech Republics. However, this is not the case in general. Belgium, Norway, Finland, Sweden, Austria and France are also in the top ten of that table.

In contrast, the most unequal ten states in the table are mostly to be found outside Europe. The UK now sits within (and near the top of) a cluster of very inequitable eastern European countries: Romania, Latvia, Lithuania and Bulgaria. Income inequality in the UK is even higher than in Israel, and higher even than South Korea. Fifty years ago the UK was one of the most equitable of OECD states. After the cold war had ended, it was not just a few Eastern European countries that became much more unequal. It was also Britain.

List: OECD countries ranked by the Gini coefficient of income inequality in 2018

- Slovak Republic 0.236

- Czech Republic 0.249

- Slovenia 0.249

- Belgium 0.258

- Norway 0.262

- Finland 0.269

- Sweden 0.275

- Austria 0.28

- Poland 0.281

- France 0.301

- Canada 0.303

- Estonia 0.305

- Greece 0.306

- Portugal 0.317

- Luxembourg 0.318

- Australia 0.325

- Spain 0.33

- Korea 0.345

- Israel 0.348

- Romania 0.35

- Latvia 0.351

- Lithuania 0.361

- UK 0.366

- Bulgaria 0.408

- Costa Rica 0.479

Note: all OECD countries for which 2018 data has been released, the most recent year available at the time of writing.

Source: https://data.oecd.org/inequality/income-inequality.htm

What should and should not be done?

All British governments since the late 1970s have failed to reduce inequality in Britain. The response of the most recent British government has been to establish a ‘Levelling Up Fund’ to target relatively small sums of money to areas that they have identified. The formulae for England includes ‘Average journey times to employment centres’.[4] In the model, this is the average journey time to the nearest place where at least 5000 people are employed.

There are places that are very affluent and others that are poorer a long way away from the nearest centre that employs 5000 people. Furthermore, there are many places in which over 5000 people are employed in which there is great deprivation and a need to level up. For many decades British governments have commissioned the creation of indices of deprivation to identify which places in the UK are most deprived. Looking at the maps of deprivation, anyone can see that, in general, deprivation tends to be higher nearer to employment centres and is quite low in places a long travel distance from them.[5]

Perhaps we should not be surprised that one of the most economically unequal of OECD states is also a place where even the interventions suggested to try to ‘level up’ are unlikely to level up but may well instead contribute to even greater unfairness in future when government funds are transferred using dubious criteria and an opaque bidding process.

It is impossible to ‘Level Up’ geographical areas while also maintaining other educational, housing and health inequalities. There remains, for instance, a huge concentration of private education spending that is concentrated mostly in the South East of England.[6] This exacerbates educational inequality locally and is detrimental to educational achievement nationally. Without educational reform to even out that spending, the opportunities for children across Britain will not become more even. That is just one aspect from numerous possible examples of one part of the domains that have been allowed to become more and more inequitable. The situation has become so bad that everything – from economic inequality, to employment, housing, education, health, family support, and so on – must be considered if we really want to level up, level out and create a more equal playing field across the UK.

There are numerous policy recommendations that could be implemented to enable true levelling up. I have touched upon just three major ones in this short piece. Research evidence from comparisons of affluent countries shows us that it will not be possible to level up without implementing, amongst other measures, each of these:

1. A more progressive system of taxation. More progressive taxation has been advocated with many researchers producing compelling evidence, including Thomas Piketty.[7]

2. Basing the allocation of funding on the right data. Evidence is increasing in the UK of pork-barrel politics, where funding is not based on need.[8]

3. Reforming education spending so that the UK is no longer the outlier state where private education funding is higher than anywhere else in Europe. In recent years state education spending across the UK has been cut, while private spending for a few children rises.[9]

References

[1] https://www.sheffield.ac.uk/news/nr/atlas-of-inequality-challenges-assumptions-rich-and-poor-1.874336

[2] http://alasdairrae.github.io/atlasofinequality/ http://alasdairrae.github.io/atlasofinequality/reports/atlas_of_inequality_18_nov_2019_FINAL.pdf

[3] https://campaignforsocialscience.org.uk/news/coming-out-of-covid-building-back-better-economics/

[4] https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/levelling-up-fund-additional-documents/levelling-up-fund-prioritisation-of-places-methodology-note

[5] https://vis.oobrien.com/booth/

[6] http://www.dannydorling.org/books/ukpopulation/Maps_%26_Figures/Pages/Chapter_3.html#5

[7] https://psmag.com/economics/what-can-we-do-about-inequality

[8] https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2021/mar/04/tories-accused-of-levelling-up-stitch-up-over-regional-deprivation-fund

[9] https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/education-45738158

About the author

Danny Dorling is the Halford Mackinder Professor of Geography at the University of Oxford. His areas of expertise include housing, health, employment, education, wealth and poverty.

The perspectives expressed in these commentary pieces represent the independent views of the authors, and as such they do not represent the views of the Academy or its Campaign for Social Science.

This article may be republished provided you place the following statement and link at the top of the article:

This article was originally commissioned and published by the Campaign for Social Science as part of its Levelling up programme.