A socially secure, fully funded Britain: evidence on Basic Income and wealth tax

The issue: ultra-insecurity and desperate outcomes

The UK is in an era of ultra-insecurity. The Global Financial Crisis, austerity politics, Brexit, the COVID-19 pandemic and the cost-of-living crisis due, in part, to the war in Ukraine, have all made it difficult for institutions and services adequately to support needs. Age-old assumptions that education and hard work lead to property, family and success have to be revised.

Those under 40 are likely to be poorer, less happy, less healthy and live shorter lives than their parents. Many of those exposed to poverty and the most extreme levels of insecurity are, in fact, those currently in full-time, insecure and low-paid employment or nominal ‘self-employment’, with many others in previously comfortable jobs exposed to fuel poverty.

The cost to society will only be fully known in years or decades to come, since today’s pressures will contribute to increases in the number and complexity of short, medium and long-term health conditions. This is creating a planning and budgeting crisis that will exacerbate challenges for population health over many years, with healthcare expenditure across the UK in 2022 estimated at £230 billion, adult social care in England alone at £26.9 billion and across the whole UK costs to society associated with poor mental health at £117.9 billion.

For the many millions of Britons who have done what society has expected of them – study, work hard, abide by the law, secure mortgages and pay into pensions – the thought that the only policy response should be increasing interest rates, making mortgages unaffordable and reducing public spending while doing nothing to tackle profiteering is anathema. The likely outcome is a significant further increase in inequality between generations and between those who live from work and those who live on passive wealth. With it, population health and social care needs will continue to grow.

The policy response: Basic Income

In this context, it is essential that policymakers invest real thought in realising the UK Government’s prevention agenda, which was incorporated into the 2019 NHS England Long Term Plan. Taking prevention seriously means tackling causes, not just symptoms and, over 40 years on from The Black Report, there is still a compelling need and logical rationale for tackling the social determinants of health and other key outcomes.

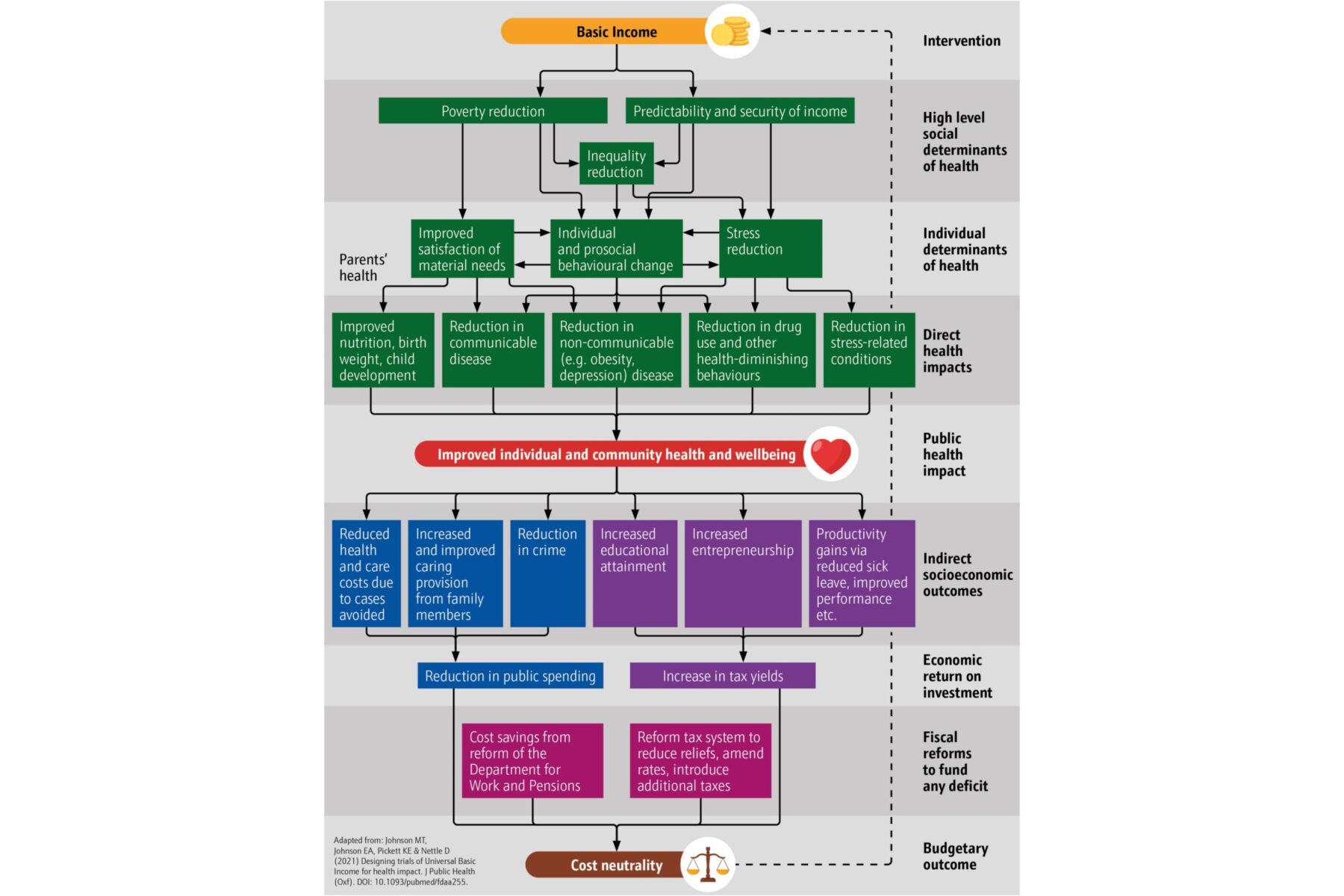

We have analysed the impact that can be had on health by providing regular, guaranteed access to a Basic Income. As our model of impact illustrates, we conclude that, if designed and evaluated effectively, Basic Income activates pathways to better health by addressing poverty, stress and health diminishing behaviour. Basic Income has been proposed by figures from across the political spectrum. The National Institute for Health and Care Research’s (NIHR) decision to invest in studies on the topic indicates a sea change in the way in which government bodies view public health and modelling ahead of trials. The Welsh Government has rolled out its Basic Income Pilot for care leavers to its first cohort and we have been involved in developing proposals for local micropilots in England.

We have found that Basic Income to promote public health is affordable, popular, and has the potential to reduce pressure on the NHS and frontline services. A fiscally neutral starter scheme would reduce child poverty to the lowest level since comparable records began in 1961 and achieve more at significantly less cost than the anti-poverty interventions of the New Labour governments. Child and pensioner poverty would fall by at least 60% each, with working age poverty down by between 29% and 75% depending on the scheme. Inequality would drop by 55% to the lowest in the world under a scheme aimed at bringing everyone up to the Minimum Income Standard, which is comparable to the Welsh pilot.

Basic Income schemes are likely to have a very significant impact as a preventive public health measure, with significant social and economic returns on investment. Between 125,000 and 1 million cases of depressive disorders and 120,000 and 1.04 million cases of clinically significant physical health symptoms could be prevented or postponed in 2023. Between 130,000 and 655,000 quality-adjusted life years (QALYs) could be gained, valued at between £3.9 billion and £19.7 billion. Based on depressive disorders alone, NHS and personal social services cost savings would be between £125 million and £1.03 billion assuming 50% of cases diagnosed and treated.

At a time of low faith in government, there is consistent evidence that citizens view the policy as credible and necessary, with levels of support ranging between 68-80% across multiple surveys at national and regional levels. It is possible to predict public preferences for Basic Income schemes based on customisable configurations and to microsimulate their costs and health outcomes using our TriplePC (Public Policy Preference Calculator) portal.

Figure 1: Basic Income model of impact

Funding the policy: wealth, carbon and corporation taxes are popular

Public reaction to Liz Truss and Kwasi Kwarteng’s “disastrous” mini-budget and Rachel Reeves’ rejection of wealth taxes both point to related concerns: put simply, the public no longer view trickle-down economics as credible and believe that increased state investment is the only means of mitigating ultra-insecurity

We found that, while citizens favour small increases to income tax over the present levels, their strong preference is for new wealth and carbon taxes and increases to corporation taxes. Unlike increases to income taxes on hard-pressed workers, annual wealth taxes and an increase in corporation taxes on profits are fundamentally affordable. Moreover, carbon taxes directly address the economically and environmentally damaging practices of profit-making companies.

Each of these taxes tackles the radical relative increase in wealth compared to wages, which has left workers facing quality-of-life deterioration that those who live off wealth have not. Using these taxes on those at the very highest levels of the income distribution to fund Basic Income improves Basic Income’s impact on reducing poverty and inequality as, although Basic Income is universal and flat, its net impact is targeted at those at the middle and lower end of the income distribution.

The political value of redistribution

Politicians who reject these funding mechanisms on electoral grounds are appealing to an ever-diminishing pool of voters who remain comfortable and insulated from our age of ultra-insecurity. The insecurity felt by so many Britons means that the social security produced by Basic Income and the redistributive mechanism of wealth, carbon and corporation taxes are extremely popular. As with Conservative commitments to and redistributive messaging around Levelling Up and Brexit in 2019, there is considerable electoral value in policies like Basic Income and tax reform. The current tax-welfare system is not working and recognising that leads logically to the need for alternatives. The evidence we have examined points us toward the policies above: without these Beveridge-style reforms, the era of ultra-insecurity is likely to lead to troubling alternatives as disaffection with political processes increases. There is still time to act.

About the authors

Dr Elliott Johnson is Senior Research Fellow in Public Policy at Northumbria University, Professor Daniel Nettle is Professor of Community Wellbeing at Newcastle University and Directeur de recherche at the Institut Jean Nicod, Professor Kate Pickett is Professor of Epidemiology at the University of York, and Professor Matthew Johnson is Professor of Politics at Northumbria University.

More information can be found on the Health Case for Basic Income website.

Photo credit: Towfiqu Barbhuiya, Unsplash